BREAST CANCER: NOT TO BE SCARED BUT TO BE AWARE

After five years of experience in the field breast and cancer imaging, common questions asked by patients and caregivers...

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most

common of all cancers in women worldwide and it is also true that this is one

of the most curable cancers if detected early. A recent study revealed that in

India, 1 in 28 women is at risk of getting breast cancer during her lifetime,

and the average age of developing breast cancer has shifted from 50-70 years to

30-50 years. Due to lack of adequate knowledge and awareness, most of the

cancers detected in India are in advanced stages (stage 3 or 4) unlike in the West,

where most of them are detected in early stages (stage 1 or 2), which can be either

completely cured or the survival can be significantly prolonged.

What are the symptoms one needs to report to

a doctor?

- Lump in the breast

- Asymmetrically enlarged breast on one side

- Abnormal discharge through nipple (other than milk)

- Painful breast

- Skin changes like thickening, redness, scaling or an open wound

- Inward pulling of nipple

- Lump in underarm area

Who are at high risk?

1. Positive family history

Blood related close family

members (mother, daughter or sister) have a history of breast cancer or ovarian

cancer.

2. Genetic predisposition:

One or more blood related

family member is found to have BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes.

3. Prior Radiation therapy to chest

How can a breast cancer be detected early?

Breast self examination:

This includes regular and

systemic examination of breast by a woman herself to look for any abnormality

or lump. It should be done at least once in a month; best time is just at the end

of menses. If any abnormality is felt, she should report to the doctor (gynaecologist

or surgeon).

After the age of twenty,

every woman should have clinical examination of breast done by a doctor at

least once in a few years or more frequently if a lump has been found.

Mammography:

Mammography should be done

yearly if a woman is more than 40 years of age. If it is normal, regular screening

should continue every year till the age of 50 years. After this, mammography

should be done at least once in 2 years.

If a woman is less than 40

years of age, it is better to avoid mammogram unless recommended by the doctor,

because it leads to a small amount of radiation exposure.

Sono-mammography/ ultrasound of breast:

Women less than 40 years of

age can have ultrasound of breast done, which does not have any radiation or

harmful effects on our body. In India, it is easily available in most of the

diagnostic centers or hospitals. So, if

someone wants screening of breast to be done without going to a clinician, they

can undergo this test directly at any center where it is available. This test

can rule out breast lump even before it is clinically palpable. If the

sonologist/radiologist feels that this test is inadequate in a particular

patient, they may recommend further tests for better evaluation.

MRI

of breast:

This test is little expensive

but extremely sensitive to detect any breast lump. It is available in most

cities of India, but this test should be done only if there is a definite

indication for it; for example, if the lump is not clearly visible on mammogram or

ultrasound and there is strong clinical suspicion, etc.

What to do once a lump has been found in the

breast?

First of all, there is no

need to panic with a mere detection of lump in the breast. Most lumps in the

breast are benign (more than 80% of all breast lumps), especially in younger

women (those with less than 40 years of age).

If the lump is of

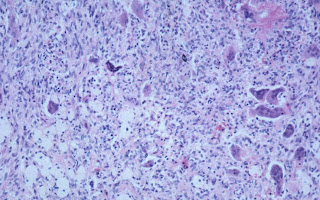

indeterminate or suspicious nature, then it needs further evaluation by doing needle

aspiration or biopsy by an experienced person and the sample is sent to

pathologist for final diagnosis (tissue diagnosis). It is advisable not to go

for major surgery of the breast without having a pre-op tissue diagnosis.

If the final diagnosis comes

as cancer of the breast, try to understand disease process rather than

believing in MYTHS. It is always better to be treated by multidisciplinary

oncology team, which consists of medical, radiation and surgical oncologists.

If the breast lump is of

benign nature and not causing much discomfort to the patient, she can be on

close follow up (screening every 3 or 6 months) or should follow clinician’s

advice.

Is there a method to prevent breast cancer?

No, there is no vaccine (as

in cancer of cervix or liver) to prevent breast cancer.